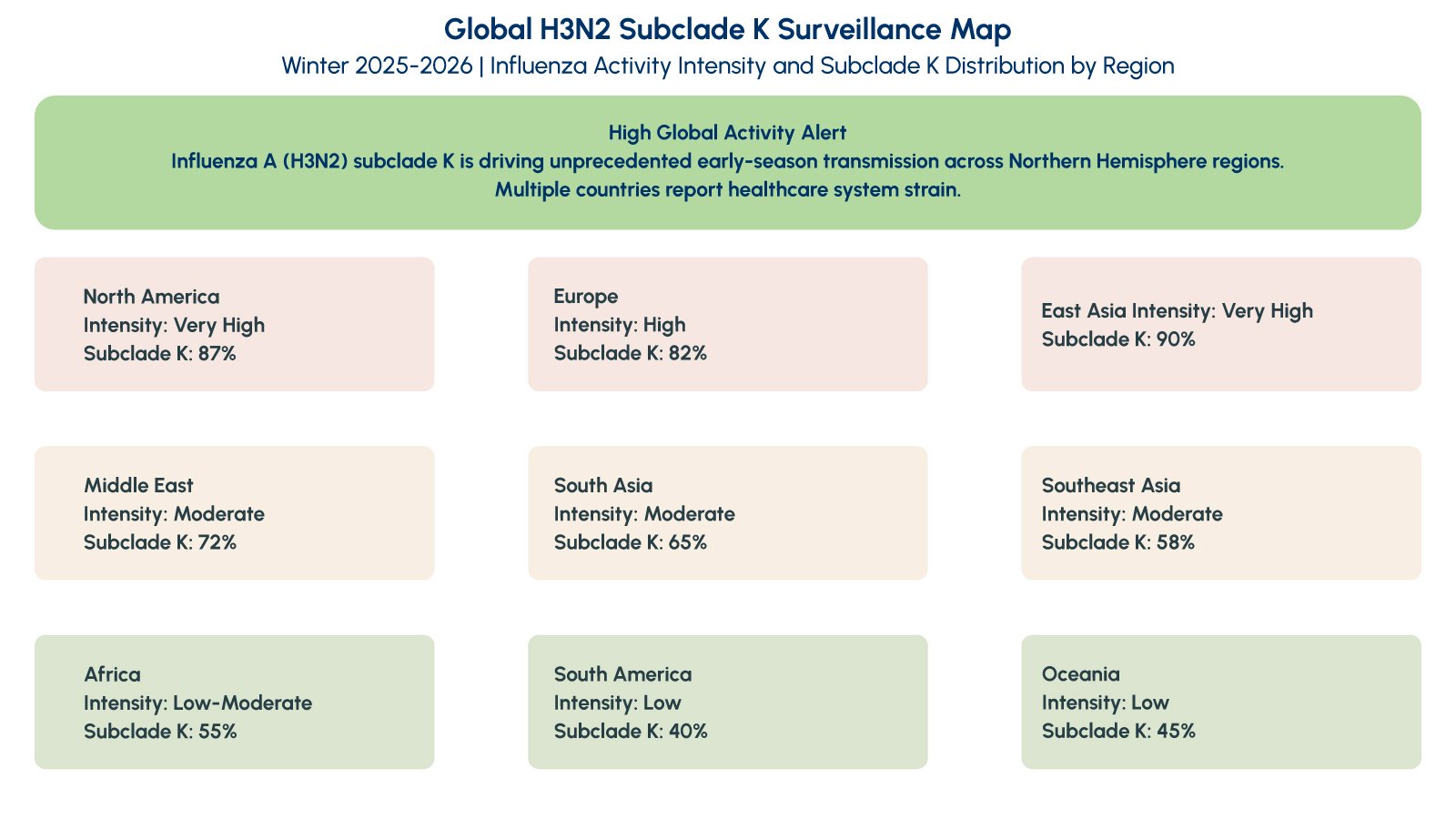

As winter 2025 transitions into early 2026, healthcare systems across multiple regions are experiencing a sharp and unusually early surge in influenza cases. Media outlets have labeled this wave the “super flu,” reflecting the scale and speed of transmission rather than the emergence of a novel pathogen. Public health authorities, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, confirm that the current surge is primarily driven by Influenza A (H3N2), with a dominant genetic subgroup known as subclade K. While this remains seasonal influenza, its epidemiological characteristics demand heightened diagnostic readiness and clinical vigilance in primary care and hospital settings.

What Defines the “Super Flu” of 2025-2026?

The term “super flu” is not a clinical or regulatory classification but has emerged as shorthand to describe the distinctive features of this influenza season. Surveillance data from late December 2025 shows that Influenza A(H3N2) accounts for the majority of circulating influenza strains, with subclade K representing a significant proportion of sequenced samples. This genetic variant emerged after the 2025-2026 Northern Hemisphere vaccine formulation was finalized, creating potential for reduced vaccine effectiveness despite immunization efforts.

The designation reflects three key epidemiological observations: rapid growth in influenza case numbers across multiple geographic regions, an earlier seasonal peak compared to typical influenza patterns, and increased pressure on outpatient clinics, emergency departments, and diagnostic laboratories. Public health experts emphasize that disease severity per individual case is not necessarily higher than previous H3N2 seasons, but the overall healthcare impact increases dramatically when transmission is widespread and occurs earlier in the respiratory disease season.

Historical patterns demonstrate that H3N2-predominant influenza seasons consistently correlate with higher consultation rates in primary care settings, increased hospital admissions among older adults, and greater diagnostic uncertainty due to symptom overlap with other circulating respiratory viruses. Understanding these patterns helps clinicians and laboratory directors prepare appropriate diagnostic strategies and resource allocation during peak transmission periods.

Clinical Significance: Why H3N2 Subclade K Demands Diagnostic Attention

Influenza A(H3N2) seasons are historically associated with more severe clinical outcomes compared to H1N1 or Influenza B-predominant years. The virus demonstrates efficient person-to-person transmission through respiratory droplets, with an incubation period of one to four days. Clinical presentation includes sudden onset fever, myalgia, headache, dry cough, sore throat, and profound fatigue-symptoms that overlap significantly with COVID-19, RSV, human metapneumovirus, and other respiratory viral infections.

This diagnostic ambiguity creates substantial challenges for clinicians attempting to differentiate influenza from other respiratory pathogens based on clinical presentation alone. Without rapid diagnostic confirmation, treatment decisions become guesswork, potentially delaying appropriate antiviral therapy or leading to unnecessary antibiotic prescribing for viral infections. The current H3N2 subclade K surge amplifies these challenges by overwhelming primary care capacity during a period when multiple respiratory pathogens circulate simultaneously.

Early identification of influenza enables several critical clinical decisions. Antiviral medications such as oseltamivir, zanamivir, and baloxavir marboxil demonstrate maximum effectiveness when initiated within 48 hours of symptom onset, reducing illness duration and risk of complications including viral pneumonia and secondary bacterial infections. For vulnerable populations-older adults, pregnant women, immunocompromised patients, and individuals with chronic cardiac or pulmonary conditions-timely antiviral therapy can prevent severe outcomes and reduce hospitalization risk.

Transmission Dynamics and High-Risk Healthcare Settings

Influenza transmission occurs primarily through large respiratory droplets expelled during coughing, sneezing, or talking, with additional spread via contaminated surfaces followed by self-inoculation of mucous membranes. Infected individuals shed virus from one day before symptom onset through five to seven days after illness begins, with longer shedding periods in immunocompromised hosts and young children. This transmission window creates particular challenges in healthcare facilities, schools, long-term care environments, and other congregate settings where close contact amplifies outbreak risk.

Healthcare facilities represent critical amplification points for influenza transmission. Nosocomial influenza outbreaks in hospitals can have devastating consequences, particularly when vulnerable patient populations in intensive care units, oncology wards, or transplant services are exposed. Rapid identification of index cases through point-of-care testing enables infection preventionists to implement droplet precautions, appropriate patient cohorting, and targeted prophylaxis before widespread facility transmission occurs.

The early surge of H3N2 subclade K during winter 2025-2026 coincides with ongoing circulation of other respiratory pathogens, creating a syndemic that strains diagnostic and clinical resources. This convergence underscores the importance of rapid, accurate differential diagnosis that distinguishes influenza from other treatable or notifiable respiratory infections.

The Critical Role of Rapid Influenza Testing in Primary Care

Traditional laboratory-based methods for influenza diagnosis include viral culture and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). While RT-PCR offers superior analytical sensitivity and provides detailed subtype identification, turnaround times of 24 to 72 hours limit its utility for immediate clinical decisions in primary care, urgent care, and emergency department settings. During periods of high influenza activity, laboratory capacity constraints further extend result reporting, creating diagnostic bottlenecks that delay patient management.

Rapid influenza diagnostic tests bridge this critical gap by providing results within 15 to 20 minutes at the point of care, enabling same-visit decision-making for antiviral therapy, infection control measures, and patient disposition. Modern rapid influenza tests utilize immunochromatographic methods to detect viral nucleoprotein antigens from nasopharyngeal or nasal swab specimens. These platforms differentiate between Influenza A and Influenza B, providing the essential diagnostic information needed to guide appropriate clinical management without requiring batch processing or specialized laboratory equipment.

The clinical value of rapid testing extends beyond individual patient encounters. Surveillance programs utilize aggregated point-of-care test data to track influenza activity in real time, informing public health responses and enabling early outbreak detection. In institutional settings such as hospitals and long-term care facilities, rapid testing supports infection control by identifying influenza-positive patients who require isolation precautions, preventing nosocomial transmission chains before they establish.

The Vitrosens RapidFor™ Influenza A/B Rapid Test: Precision at the Point of Care

The Vitrosens RapidFor™ Influenza A/B Rapid Test addresses the critical need for accurate, rapid influenza detection across diverse clinical settings during high-activity seasons. This immunochromatographic assay simultaneously detects and differentiates Influenza A and Influenza B antigens from nasal swab or nasopharyngeal swab specimens, delivering results in 15 minutes without requiring instrumentation or specialized technical expertise.

Key Features and Benefits:

- Rapid Diagnostic Turnaround: Provides results within 15 minutes, enabling same-visit clinical decisions regarding antiviral therapy initiation, infection control implementation, and appropriate patient disposition

- Differential Influenza Detection: Distinguishes between Influenza A and Influenza B, supporting appropriate antiviral selection and contributing to epidemiological surveillance of circulating influenza types

- Point-of-Care Accessibility: Requires no instrumentation or complex laboratory infrastructure, making it suitable for physician offices, urgent care facilities, emergency departments, pharmacy testing programs, and resource-limited settings

- Validated Against Circulating Strains: Designed to detect currently circulating Influenza A subtypes including H3N2 variants monitored by global surveillance programs, ensuring diagnostic reliability during strain evolution

- Simple Specimen Collection: Compatible with nasal swab collection methods that minimize patient discomfort and facilitate specimen acquisition across all age groups from pediatric to geriatric populations

- Clinical Decision Support: High specificity minimizes false-positive results that could lead to unnecessary antiviral therapy or infection control interventions, while sensitivity appropriate for symptomatic patients supports timely diagnosis

- Workflow Efficiency: Single-test format with rapid turnaround reduces laboratory batching delays and supports flexible testing schedules aligned with patient flow patterns in high-volume clinical settings

The RapidFor™ Influenza A/B test prioritizes clinical utility during high-burden influenza seasons when rapid triage and accurate diagnosis are essential. By providing actionable results while the patient remains in the clinical setting, this platform supports evidence-based decision-making that improves patient outcomes, reduces unnecessary antibiotic prescribing, and enhances infection prevention efforts across healthcare facilities.

How to Use the Vitrosens RapidFor™ Influenza A/B Rapid Test

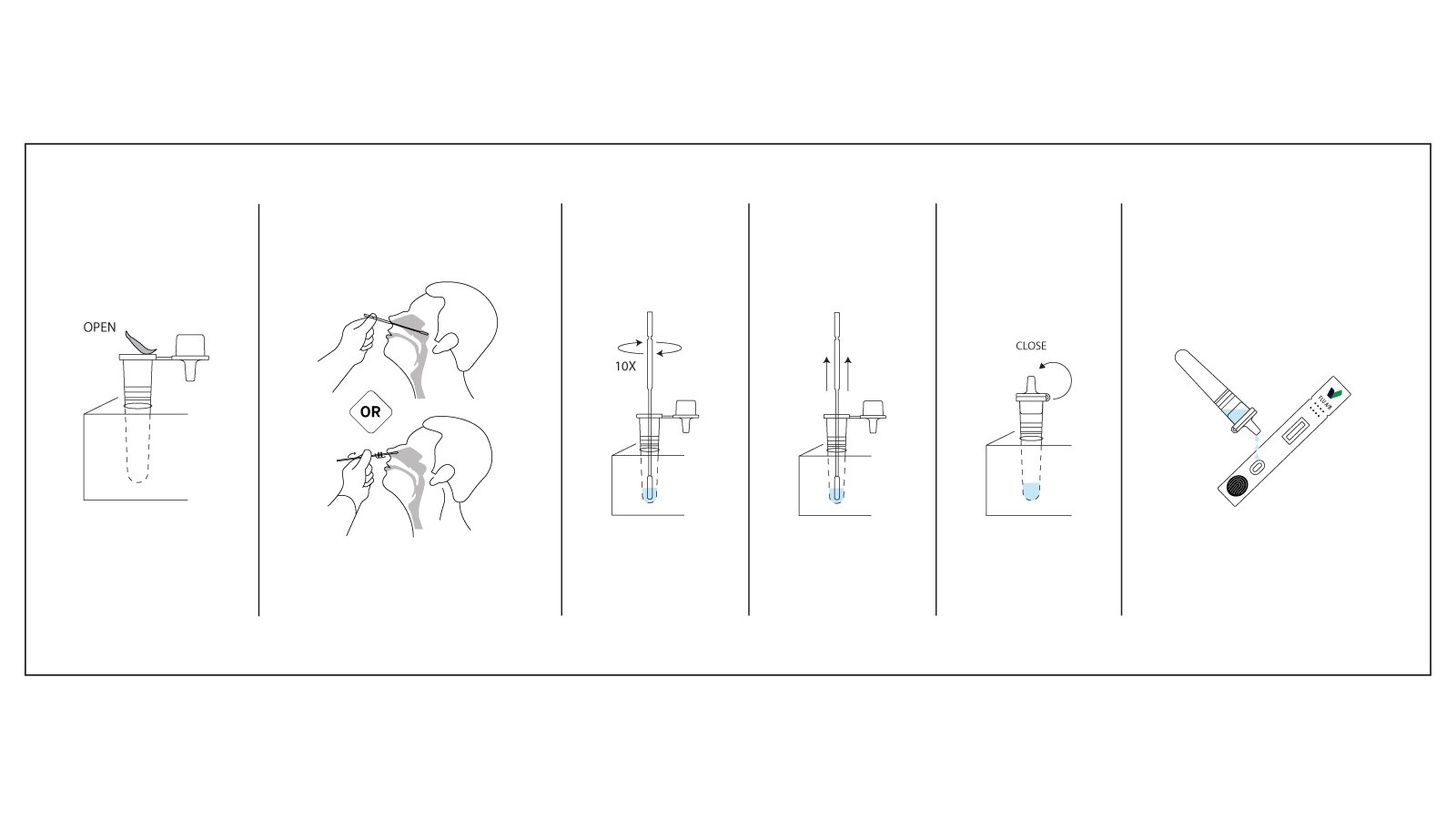

Using the Vitrosens RapidFor™ test kit is straightforward, requiring minimal training and equipment:

- Specimen Collection: Collect a nasal swab or nasopharyngeal swab specimen from the patient using the provided sterile swab. Insert the swab into the nostril and rotate it against the nasal wall several times to ensure adequate cellular material and viral antigen collection.

- Sample Preparation: Insert the collected swab into the extraction tube containing the assay buffer. Rotate the swab vigorously in the buffer solution at least five times to release viral antigens into the solution. Squeeze the tube from the outside while removing the swab to extract maximum sample volume.

- Test Application: Remove the test cassette from its protective foil pouch and place it on a clean, flat surface. Invert the extraction tube and dispense exactly three drops of the extracted sample into the specimen well of the test cassette, ensuring drops fall freely without the dropper tip touching the cassette surface.

- Incubation: Allow the test to develop for 15 minutes at room temperature. Do not disturb the cassette during the reaction period. Avoid reading results before 15 minutes to prevent false-negative interpretations or after 20 minutes to ensure result stability.

- Result Interpretation:

- Positive for Influenza A: Both the control line (C) and Influenza A test line (A) appear as visible colored bands, indicating active Influenza A infection requiring clinical management and potential antiviral therapy

- Positive for Influenza B: Both the control line (C) and Influenza B test line (B) appear as visible colored bands, confirming Influenza B infection

- Negative Result: Only the control line (C) appears, suggesting influenza is not detected. Clinical judgment should guide whether additional testing or alternative diagnosis is warranted based on symptom presentation and epidemiological context

- Invalid Result: No control line appears, indicating improper test performance. Repeat the test using a new cassette and fresh specimen

Results should be documented immediately in the patient record and communicated to the ordering provider for clinical action. Any line intensity, regardless of how faint, should be considered positive if both the control line and test line are visible. Store unused test cassettes at room temperature (2-30°C) in their original sealed pouches. Discard used test materials according to biohazard waste protocols consistent with infectious material handling procedures.

Transforming Respiratory Diagnostics During High-Activity Seasons

The value of rapid influenza testing extends beyond isolated patient encounters to support comprehensive respiratory diagnostic strategies and public health preparedness. During seasons characterized by high H3N2 activity such as the current 2025-2026 surge, clinical algorithms that incorporate point-of-care influenza testing alongside multiplex respiratory panels and COVID-19 testing create diagnostic pathways optimized for patient flow, resource utilization, and infection control.

Enhanced Clinical Decision-Making: Rapid differentiation between influenza and other respiratory viruses guides appropriate antiviral therapy while preventing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for viral syndromes. Same-visit diagnostic clarity enables clinicians to provide definitive treatment recommendations rather than empiric approaches based on syndromic assumptions.

Infection Prevention and Control: Early identification of influenza-positive patients through point-of-care testing enables prompt implementation of droplet precautions, appropriate room placement in healthcare facilities, and targeted chemoprophylaxis for exposed high-risk contacts in institutional settings. This diagnostic speed prevents nosocomial transmission chains before they establish in vulnerable patient populations.

Public Health Surveillance: Aggregated point-of-care testing data provides real-time influenza activity monitoring that supplements traditional laboratory-based surveillance systems. Rapid reporting from distributed testing sites enables earlier detection of outbreak trends, geographic spread patterns, and potential emergence of antiviral resistance, supporting timely public health interventions.

Resource Optimization: By reducing diagnostic uncertainty, rapid testing minimizes unnecessary chest radiography, extensive laboratory workups, and empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Healthcare systems implementing standardized rapid influenza testing protocols report improved antibiotic stewardship metrics, reduced emergency department length of stay, and enhanced patient satisfaction through same-visit diagnostic resolution.

Healthcare delivery systems that maintain robust rapid influenza testing capacity demonstrate improved preparedness for seasonal surges and enhanced ability to manage concurrent circulation of multiple respiratory pathogens. The diagnostic clarity provided by point-of-care testing transforms influenza from a presumptive syndromic diagnosis to a confirmed entity that enables evidence-based clinical pathways.

Why This Matters for Diagnostic Distributors and Healthcare Systems

For diagnostic distributors, clinical laboratories, and healthcare providers, the current H3N2 subclade K influenza season highlights several recurring realities that shape respiratory diagnostics strategy. Influenza continues to evolve genetically through antigenic drift, but well-validated rapid antigen tests maintain the ability to detect these variants because they target conserved viral nucleoprotein antigens rather than variable surface proteins. This stability ensures diagnostic reliability across seasonal strain variations.

Diagnostic preparedness during high-burden respiratory seasons depends on reliable, scalable, and easily deployable testing solutions that integrate seamlessly into existing clinical workflows. Healthcare systems that maintain adequate rapid testing capacity before seasonal surges demonstrate superior ability to manage patient volumes, implement appropriate infection control measures, and support public health surveillance objectives. Confidence in product coverage and performance supports uninterrupted supply chains and clinical trust during periods of peak demand when testing volumes may increase five to tenfold.

Rapid influenza testing is no longer optional seasonal insurance but represents a core component of comprehensive respiratory diagnostics portfolios. The convergence of influenza, COVID-19, RSV, and other respiratory pathogens during winter months creates sustained demand for point-of-care testing platforms that enable differential diagnosis within a single patient encounter. Healthcare systems are increasingly adopting algorithmic approaches that combine rapid influenza testing with other point-of-care platforms to achieve comprehensive respiratory pathogen coverage.

Conclusion

The 2025-2026 influenza season characterized by H3N2 subclade K demonstrates how rapidly seasonal respiratory viruses can strain healthcare systems when transmission accelerates and peaks earlier than anticipated. While the term “super flu” reflects public concern and media attention, the clinical response remains grounded in fundamental principles: accurate diagnosis, timely treatment decisions, appropriate infection control, and effective public health surveillance. The convergence of epidemiological factors-early seasonal surge, potential vaccine mismatch, and concurrent circulation of multiple respiratory pathogens-underscores the persistent importance of robust diagnostic infrastructure.

Rapid influenza testing at the point of care represents an essential capability for frontline clinicians managing respiratory illness during periods of high disease activity. The Vitrosens RapidFor™ Influenza A/B Rapid Test provides healthcare professionals with a reliable, validated, and user-friendly diagnostic solution that bridges the critical gap between clinical suspicion and confirmed diagnosis. By enabling same-visit results that directly inform antiviral therapy decisions, infection control measures, and patient counseling, rapid influenza testing transforms clinical workflows and supports improved patient outcomes during challenging respiratory disease seasons.

To request technical documentation, evaluation kits, or discuss distribution opportunities for RapidFor™ influenza diagnostics, contact sales@vitrosens.com and strengthen your respiratory testing portfolio for the seasons ahead.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report, 2025-2026 Season. Accessed January 2026.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Influenza Update: Global Surveillance and Vaccine Composition Reports. 2025-2026.

- Petrova VN, Russell CA. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2018;16(1):47-60.

- Uyeki TM, Hui DS, Zambon M, et al. Influenza. The Lancet. 2022;400(10353):693-706.

- Chartrand C, Leeflang MMG, Minion J, et al. Accuracy of rapid influenza diagnostic tests: a meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156(7):500-511.

- Belongia EA, Simpson MD, King JP, et al. Variable influenza vaccine effectiveness by subtype: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(8):942-951.